My Olds Super tenor as been at David’s shop for just over a couple of weeks now, and he is working hard at restoring this beauty to its original glory. Before David took it apart, I noodled around on the horn as best as I could for him, demonstrating the tone of this unique instrument. Based on what it sounded like in its leaking, mouldy state—with my Dukoff S7 MP, and my Légère Signature Series reeds—we discussed my pad and reso options.

I opted to go with black roo pads and flat, sterling silver, Reso-Tech resonators that are a bit oversized—since they are for a Selmer Mark VI bari. The look and sound should be stunning when complete.

The horn will also be getting new springs. Since I’m not a fan of blue needle springs, we’re going with piano wire.

I took my camera with me, and snapped a whole bunch of pics that will eventually get incorporated into the upcoming Olds Super pages for my website. In the meantime, they might be of interest to those following the thread I started on the brand on SOTW, and for anyone else who has an interest into arguably the most beautiful—certainly the most Art Deco—saxophone ever designed.

Some interesting & unique features of the Olds Super

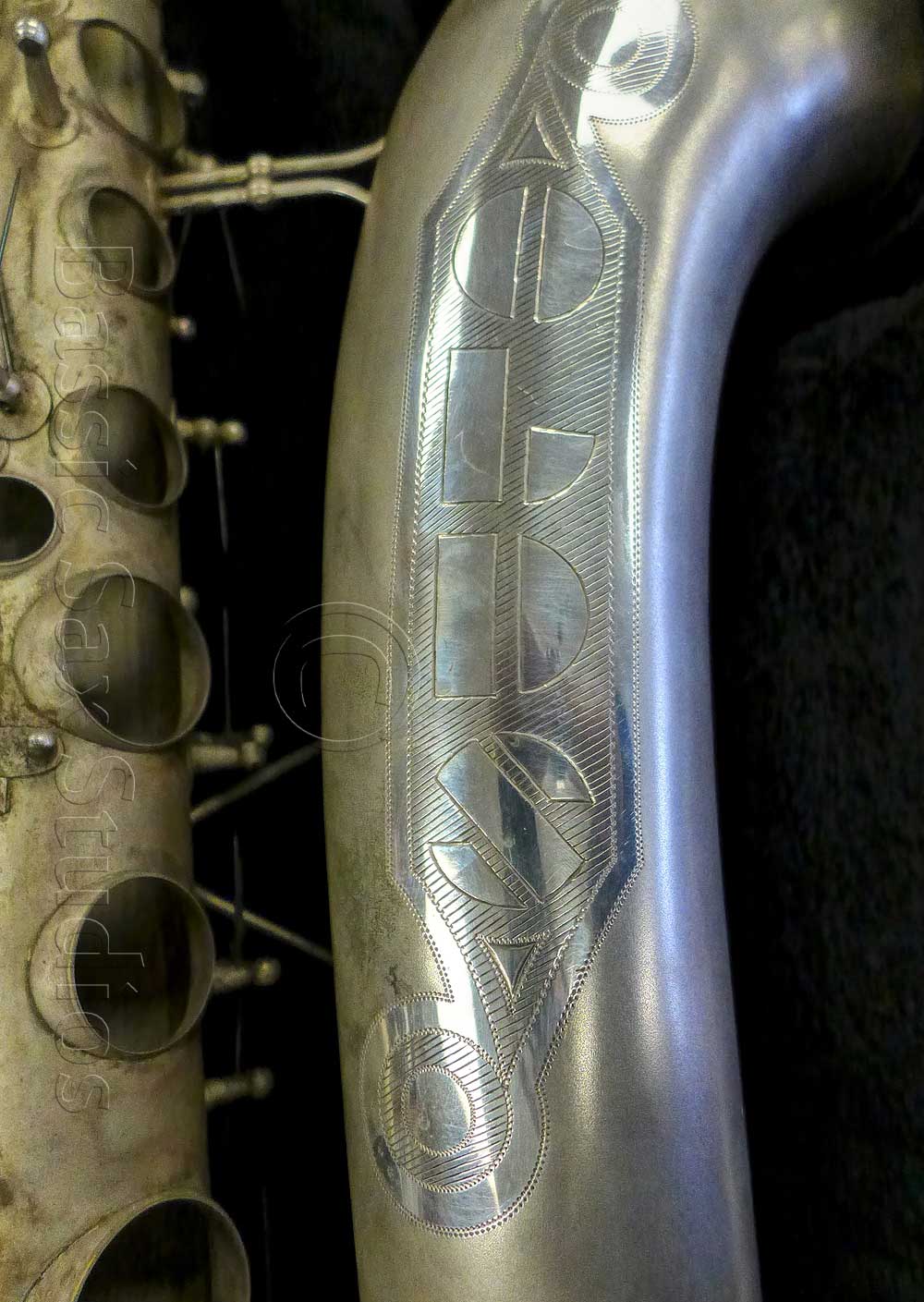

The “engraving”

One of the most Art Deco features of the horn, is the bell engraving… But not so fast… It is not engraving at all.

One of the most Art Deco features of the horn, is the bell engraving… But not so fast… It is not engraving at all.

This is something I noticed while at WWS. When I first picked the tenor up out of its stand, I noticed the bell seemed a bit flatter on the right side. At first I thought the horn had had some dent work done.

However, when I compared it to the Olds Super alto that Chadd had already completed a restoration on, I found the same flatness on the alto bell’s right side. It turns out that the engraving isn’t engraving at all.

The word Olds appears to have been stamped, rather than engraved on the bell of these instruments. It would seem that Olds—or whoever made them if you believe that they were outsourced—did not employ any engravers.

Inline tone holes

Since I only play vintage horns, I don’t get too caught up in what kind of key mechanisms a horn has, or whether the horn has inline or offset tone holes. With offset tone holes, the right hand tone holes are closer to the player’s hand, thus making the horn more ergonomic.

However, before Selmer came up with the idea to move the right hand tone holes closer to the player’s hand in the late 1940s1, having all the tone holes line up one under another was the norm. The Olds Super (circa 1940) is still from the era when inline tone holes was standard.

Speaking of tone holes…

According to a few different Martin aficionados and repair techs, although bevelled, the Olds Super’s tone holes do not resemble any that Martin produced.

Now I must confess, as much as I love my Martin Handcraft tenor, and my Committee III bari, I have never done an in-depth study of Martin tone holes. The above-noted thread on SOTW really was an eye-opener for me about how many different styles of tone holes Martin manufactured.

However, the Olds has tone holes that look nothing like Martin, or any other manufacturer’s bevelled tone holes.

Keys

Speaking of features that resemble no other manufacturer’s, the keys on the Olds Super are one of this brand’s most defining features. The have a circular indent, much as we would see on a flute. These dimples too are one of this brand’s most defining, and beautiful features.

This is what this dimple looks like in the key cup.

While photographing this key cup, I noticed what I presume must be a part number on the key. It’s worth nothing that this key is the only one with such a number on it that I could see.

I wonder what 20T refers to? Why are not all keys numbered? Does an alto have an A stamped on it? So many questions…

Not your average roller

I’m not sure anymore if it was David, Chadd, or I who first noticed this, but the rollers on the Olds Super tenor sax appear to be made of ivory.

This goes along with the general opulence that the horn has. Even the pearls are not the same old, same old. Unfortunately they do not photograph well, but they have a green/blue hue to them that I have not seen before on any sax I have held in my hands.

Octave key mechanism ala Hammerschmidt

Having owned Hammerschmidt saxophones for more than a decade now, I am intimately familiar with their wishbone-style octave key mechanism. And while other companies such as Dolnet, and even A.E. Sax and some early Selmers, may have used this wishbone-style octave mechanism, one thing that I immediately noticed about the Olds Super is that its octave key mechanism design was pretty much identical to those we see on the German-made Hammerschmidts.

Furthermore, the left thumb rest and octave key lever are basically the same shape on the Olds Super as they are on the Hammerschmidt.

I am not suggesting that Hammerschmidt made the Olds Super. (Although Hammerschmidt did make horns with bevelled, not just rolled tone holes, but I digress…)

Some crazy speculation, and some actual empirical facts

1. Since Olds was not a saxophone manufacturer, it is possible that they outsourced some of the part production to other companies. These companies could have manufactured the parts—which were designed in consultation with employees at Olds—and then shipped said parts to the Olds factory in Los Angeles. The saxophones could have then been assembled in LA by Olds employees.

2. As some very learned techs have pointed out on the SOTW thread, the Olds Super and the Committee II are nearly identical in many respects. This is how experienced vintage sax tech, Jorns Bergenson, described these 2 instruments:

Helen, there are not are just few similarities between these horns. Most of the important stuff is exactly the same. Same design made with the same machinery. I don’t want to come on too strong here with my opinions but I’ve had a Super and a Comm II side by side and to me they are basically the same horn. There was no doubt in my mind. More facts that point to this:

- The necks are interchangeable. Same dimensions. Same inner volume. The octave vent is in exactly the same place. When I put the Comm II neck on the Super, it was a perfect match. Intonation was the same with either neck. That simple test says a lot about the acoustic design of these two horns being the same.

- 90% of the keys are identical except for the key cups. The keys were at the least made by the same machinery.

- Only the octave key is different between these horns, but the same octave mechanism was used on another Martin-made horn (Reynolds Contempora).

- The key guards and braces, while not exactly the same as the Comm II, are similar is design and construction.

- The key posts and pillars are exactly the same (with a couple of minor exceptions) and are placed in exactly the same places.

- The only repair that I had done to the Super that was in my shop some years ago was to replace the low Eb tone hole which had been knocked loose and lost. I used a tone hole from a Martin tenor and the tone hole was an exact replacement. Same inner and outer diameter. Same height. Same contour. That also means that the body tubes were exactly the same down there.

- The differences between these horns are mostly cosmetic.

3.Following this line of thinking to its logical conclusion then, we could postulate that:

- Martin was heavily involved in the creation of the Olds. However, Olds likely did employ designers in the creation of the Super.

- Body tubes could easily have been made by Olds at their factory, since they were a brass instrument maker and quite used to making tubing. Although those could have been outsourced to Martin as well. (The Committee II was made from 1939-1942, so timing fits, since it roughly fits into the period when the Olds Super was produced.)

- Tone holes were Martin-inspired, perhaps even built by Martin. However, they may have been designed by Olds. Or at the very least, specifically for the Super.

- The key work was specifically designed for the Olds Super.

- The octave key assembly is the part of the sax that is a bit of an enigma. Although it resembles that of Hammerschmidt, that company didn’t relocate to Germany until after WWII, and wasn’t known for building saxophones until 1952. It is true that Hammerschmidt did build some prototype saxophones while still in Egerland (now part of the Czech Republic), but unfortunately I haven’t been able to find any good images of horns from that period that show the saxophones’ octave mechanisms. Therefore it is impossible to say at this time if Olds was Hammerschmidt-inspired or vice versa.

Interesting fodder for thought and conversation. All kinds of things come to mind actually–things that go way beyond the scope of an article on the progress of my Olds Super tenor’s rebuild.

In conclusion then…

The holidays have slowed down the arrival of the last of needed supplies, so my horn will be ready in the first couple weeks of January. I know I’m not the only one who is looking forward to trying it out. My tenor partner in The Moonliters has been asking when I’m bringing it to rehearsal, and my sax-playing friends who I get together with outside of a band, are also asking when it will be ready.

Yup, I’m not the only one looking forward to the big reveal. All in all, I suspect 2018 is going to be a Super year. 😉

____________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Source: Saxpics.com: The Selmer Super Balanced Action

Mary Christmas Helen,

Today I would like to present a Christmas theory on the dimples in the Olds key-cups.

Maybe they are only for aesthetics and maybe they have a purpose.

Generally pads are slightly oversized to the key-cups. This makes them concave, which gives a good contact area to the the outer rim of the tone-holes.

To improve the contact area the tone-holes can be fluted or rounded.

In the Olds key-cups the dimples reduce the concave shape of the leather so it makes sense, only in this case, to have a flat rimmed tone-hole.

This theory is as hard to disprove as most saxophones theories are.

Therefore it is more important how the saxophone sounds than which theories we believe in.

Not that it is very important, but like you I am a disbeliever in the special qualities of blue steel springs. We share this with the largest part of the industrial spring world.

I do think blue steel springs as commonly implemented* make the keywork feel different under the fingers — but not necessarily better. It’s more a matter of what you’re used to. Switching back and forth can be mildly annoying, but a few minutes of playing and you’ll forget about the difference and just play. If you’re switching every two minutes like in a pit, then there is something to be said for keeping things uniform.

*tapered and needle sharp — I wonder how it would change things to either taper stainless springs, or not taper blued steel, and then compare.

To compare them you need to have two instruments on which all keys move with the same applied force, length of movement and moved mass. Then there is not much difference and the mildly annoying switching effect disappears.

In the process of bending springs to get the right force profile you will notice that blue springs loose there elasticity easier then top notch stainless springs. This is the main reason why in the industrial spring world you hardly find blues springs anymore.

When you do not bend them too often they are alright.

The bad name of stainless springs comes from the first generations of Asian saxophones . It was one of the visible differences.

Now the Asian sellers are the first to mention they use blue springs.

For me it signifies a minimum acceptable level of quality, but not a top level.

Famously, Yamaha used stainless steel springs in the YAS-21 and -23 (and YTS-) and possibly other models that I haven’t actually played, and the feel _is_ different between, say, a 21 and a 62. The keywork itself is only minimally different.

No matter which I pick up and play for a while, I’ll end up saying “OK, I like this”, and if asked to switch mid-session, it will feel strange. A few minutes later I’ll be back to “OK, I like this”, no matter which one I’m holding.

I think part of stainless steel’s bad rap is that they’re almost always lengths of wire, cut and crimped, and all the same thickness (or maybe two or three gauges across the instrument). Meanwhile, there is a wider variety of blued steel spring profiles to choose from. This means the keys can be designed without too much thought as to the springing, because that can be cobbled together afterward. If using stainless, you have to think about that stuff from the beginning because you can’t just pick something out of a parts bin and have it bail you out on your decision-making.

In other words, stainless steel works fine, if and only if the instrument is engineered from the ground up to use stainless steel springs. Merely dropping them into an instrument designed for blued steel will feel uneven and wrong.

It is a good idea to compare two Yamaha’s and

I am not surprised that people can feel a difference.

The human touch is extremely sensitive.

Last year I read a paper on people detecting a layer of one molecule thick by touch.

Call me insensitive, when I do not have the right diameter of stainless springs…. I use blue steel springs.

Couldn’t agree more. I don’t know what kind of springs I have in what had been my primary tenor for 20+ years: my Mark VI. Whatever they are, my tech in Halifax loved them, and told me never to change them. EVER. He figured they would outlast me, and likely the next player on the horn. They are most certainly not blue needle.

My Zeph that I got from Sarge at WWS also has no blue needle springs. Sarge set it up beautifully for me, taking into account my slight neuro deficits in my fingers. It is perfectly responsive to the touch, and stunningly easy to play. Furthermore, it seals perfectly, and the tension on whatever kind of springs are on the horn, has remained 100% constant after nearly a decade of being my primary tenor–meaning constant use as my rehearsal and gigging horn.

I do own horns that have had blue needle springs scattered here, there, and everywhere as replacements. There is a minor difference in the way the keys operated by those springs feel, compared to those sans blue needle. I certainly play the horns regularly, and don’t mind them at all. It is just part of the way horn X plays compared to horn Y. No big deal.

That said, since what we are doing is restoring this lovely Super, and rebuilding it from the ground up mechanically, David suggested we replace all of the springs to keep things consistent. Also, since quite often older springs can be better in quality than the newer ones available, it strikes me that using piano wire was a good alternative. Furthermore, it would keep the feel more consistent with my other primary tenors.

Like the reso and pad choices I made for the Super, I consulted with my very experienced tech—whom I trust implicitly. David knows his stuff, and has worked on vintage saxophones since back when his career started in the workshop at Buffet in Paris in the late 1980s. All the overhauls and/or restorations he has done on my saxes are fantastic, and I usually gave him license to do what he felt was best for the horn.

In this case, we talked about the options, and did a “best guess” scenario of what would be the likely results. However, with so few Supers out there, the final result will be a mystery until it is completed in a couple of weeks. In the meantime, the suspense is kind of fun too.

I wish you much happiness with your new addition to the stable.

I, on the other hand, have crossed over to the dark side of G.A.S. and am now the owner of a Stratocaster-style electric guitar. It’s not my first one, although it’s the only guitar I have currently. I assembled it from a kit, and ordered parts from a range of sources (all but two of which are in China) intended to make it sound much better than it deserves. Even after ordering the parts upgrades, I’m still in less than $120 on this build. It’s not the first time I’ve taken a guitar to bits, attempted to improve it, and then reassembled it, but it’s the first time I’ve _started_ with nothing but a pile of parts.

I still have blue paint under my fingernails where I scratched holes in my gloves and didn’t realize it. I also am completely lacking the necessary left-hand calluses since I haven’t actually possessed a guitar in the past four years. This is the only one I intend to get, since it will be used only in the home studio, but that doesn’t stop me from drooling over a Les Paul Standard the same way you undoubtedly do every time your tech gets something interesting on the bench.

I can only advise you not to go down the guitar rabbit hole. Those guys practically _invented_ G.A.S.

The leader of the last blues band I played in is a guitar player, and plays exclusively on Les Paul guitars. He was without a doubt, one of the best blues guitarists that I have ever heard, and had the pleasure to play with.

Art has a gold top (that doesn’t get used for shows), as well as well as another one that is burgundy in colour. (Sorry, not up on my guitar stuff, so I don’t know what model it is.) I was always afraid to touch his gold top—much like I was afraid to touch the Grafton sax that came to visit me along with its owner. The primary differences being of course that the gold top is more than hundred times more valuable than the Grafton, but not fragile. 😉

Les Pauls are stupid easy to identify, usually. They (like most Gibson and Epiphone and knockoff guitars) have a bell-shaped plastic plate on the headstock that covers the truss rod, and on this plate, they silk screen the name of the model. Of course that assumes it’s original, but it’s unlikely someone would want to harm the value of a Gibson LP by putting non-matching parts on it (that don’t actually improve it, at least). People up-marking Epiphones is another matter entirely, and of course there are straight-up fakes on the market now. By fake, I don’t mean they’re not Les Paul models, they actually are. But they’re Epiphone at best, and more likely Epiphone _rejects_, with the Gibson name on the headstock. You can pick this out pretty quickly. On a real Gibson, the binding on the sides of the neck has bumps that cover the ends of the frets. On an Epiphone, the binding does not cover the ends of the frets. There are other visual (and electrical) differences, but that’s an easy one to check for.

Personally I’d be happy with a well set-up Epiphone LP with upgraded pickups. Just like with saxophones, a well set up midrange guitar will play better than a custom shop guitar that was either not finished or ham-fisted at the factory. Also like saxophones, don’t expect to hold your resale value unless it’s one of the Big Names or a coveted rarity. _Unlike_ saxophones, artificially aged guitars are not yet out of fashion. We call it “vintifying”, they call it “relicing” (that’s relic-ing, not re-licing!).

I don’t think it will be much longer (basically, whenever the last of the parts arrives, plus a couple days) before I could hand my guitar to an expert player and get a positive review. It already sounds and plays much better than I had hoped for the price, not counting the 20-something hours I’ve put into working on it (which an expert could have done in three at most). It’s been frustrating at times, but fun, and there is a certain satisfaction in playing an instrument that is great because I personally made it great. I think that spans all genres and all instruments.

The physics on the different feel of blue springs puzzles me. The last four centuries metal springs have been measured frequently and accurately for deviations on Hooke’s law. Aluminium is a known exception. But stainless steel, and blue steel springs (low carbon steel) should behave in the same way. So why is it possible to feel a difference?

My guess is that blue needle springs are used nearer to their deformation point.

Here Hooke’s law (deformation is linear with force) does not apply.

Consequently they loose there rigidity faster than springs which are used far below there deformation point.

Sorry for the scientific interlude, but these details bug me.